We drove into the gathering darkness of Mpumalanga province, on and on along the dark roads, the occasional fire to light the distance; on towards Piet Retief; past Piet Retief to Ermelo where we stopped off at a Wimpy’s for a burger. The bright interior could, absurdly, have been anywhere in our globalised, corporate world, but outside as we sat there, the only customers on a dead Tuesday night, the huge African sky loomed over all – this town which had been razed to the ground during the Boer War.

On we went, as satisfied as one can be by such fare. On to Gauteng province, to Johannesburg, to Linden, to 65 Seventh Street, to 119 Denmyr – to home.

Can I thank ever enough my guides and my friends on this journey?

Next day they, poor fellows, were off to work. Up at 4.30 am, shirts to iron, minds to bend back to the disciplines of the engineer – rain run-off of roads to calculate, force of tides on harbour moles to be considered.

I on the other hand, was off to Soweto.

We arranged it that morning on the phone. I would be waiting outside some swank hotel in Johannesburg at 9.00 am and my guide from Johnny’s Face to Face Tours would meet me. And so it was.

Sfisio was a Zulu and he lived in Soweto. We drove the short miles in his car to Soweto – the ‘south western township’.

The Anglican cathedral is the focal point of the city layout of Christchurch. It sits there in the centre of Cathedral Square in the centre of that squarest of cities.

I remember its interior as having gas heaters affixed to each of its great, gloomy pillars. These gave the place a damp gassy smell which, along with the faded flags of empire hanging in shadowy corners, memorials to boy scouts and long-dead imperial scoundrels, seemed to sum up all that was dead and irrelevant.

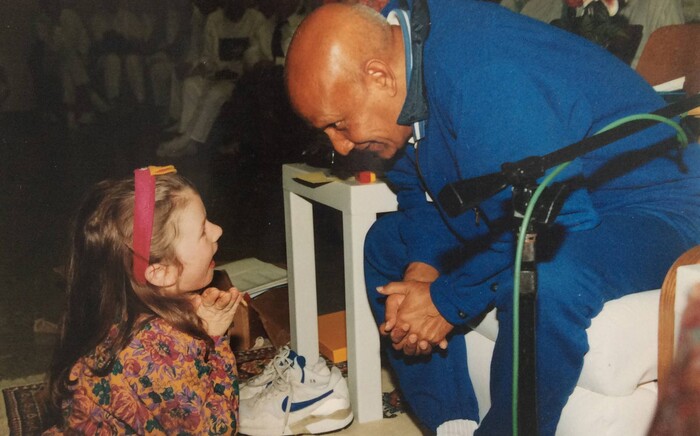

Once, though, I found myself in that building standing at the very back, pressed in amongst the rest of the eager, seething, excited crowd held transfixed by a tiny, brilliant focus of light and life at the distant pulpit – an Anglican archbishop: the Anglican Archbishop of Cape Town – Desmond Tutu.

Soweto is the only city to have given two Nobel Peace Prize laureates to the world – they lived on the same street. This vast sprawling ‘township’ where once the abominable laws of the nation stipulated that the majority must live in poverty and oppression for the sin of being natives in their own country, this miserable place has brought forth men like Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu who followed Chief Albert Luthuli into the ranks of South African Nobel Peace Prize laureates.

We drove past the house of Desmond Tutu, though Sfisio said he spent most of his time out of the country. We went to the little house where Nelson Mandela had lived before he was arrested and imprisoned for 27 years on Robben Island. I went in. It was small and drab and unimpressive, yet within these mundane walls the planet’s most respected man had once lived the life of an enemy of the state.

Soweto was huge and of an extraordinary diversity. There were mansions more impressive than anything I saw in Johannesburg: there were vast swathes of hovels of the rudest kind overhung with wood smoke and the smell of poverty. Everywhere there were people. A man selling mag-wheels did so on the side of the road, the mechanic fixing cars did so on an open spot of ground.

It was noticeable that the oppressive security that was so conspicuous to the visitor in Johannesburg – where every building is ringed by an eight-foot wall topped with a ten-strand electric fence set about with barbed wire and spikes – was not evident in Soweto even in the most extravagantly prosperous areas. ‘In Soweto,’ Sfisio explained, ‘we talk to our neighbours.’ There are eleven official languages in South Africa, he explained. ‘In Soweto it pays to speak as many of them as possible.’

In 1955 the Freedom Charter, which was to become, long years later, the blueprint for a free and democratic South Africa, was signed in Kliptown, Soweto. We went to the Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication, a vast, strangely compelling space whose focal point is a structure that houses the declarations of the Freedom Charter:

The people shall govern

All national groups shall have equal rights

The people shall share the country’s wealth

The land shall be shared amongst those who work it

All shall be equal before the law

All shall enjoy equal human rights

There shall be work and security

The doors of learning and culture shall be opened

There shall be houses, security and comfort

There shall be peace and friendship

Everywhere the skyline is dominated by the ‘twin towers’ – vast cooling towers of the huge power station that is right in the centre of Soweto. It was built in the days of apartheid to provide power – to Johannesburg.

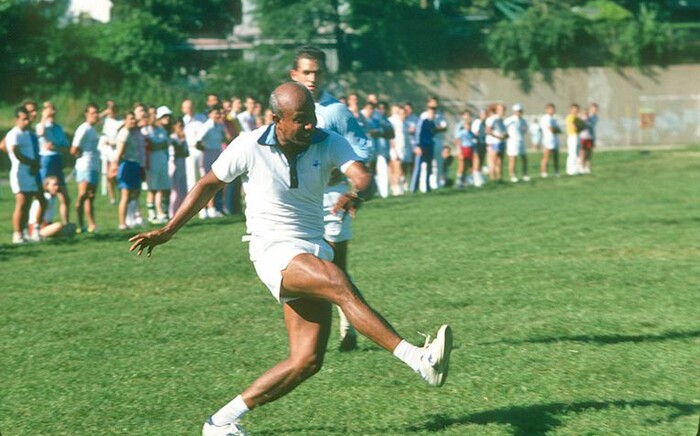

We passed these and the vast Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital. Sfisio pointed out to me the many playing fields. South Africans are obsessed with soccer he said. He said it several times as if to reinforce to the New Zealander that rugby was not the game that the majority of South Africans cared for.

We passed the house of Winnie Mandela who Sfisio said earned a lot of respect for still living in Soweto.

Once white people visited Soweto, armed with whips and rifles, in those huge yellow, high-wheeled armoured personnel carriers that we used to see pictures of raising dust as they wheeled amongst angry crowds. I thought of that as I dove around in a nice Japanese car, the guest of a local.

In 1976 the school children of Soweto gathered to protest having to learn in the Afrikaans language. The response of the armed defenders of apartheid was unimaginatively standard – they opened fire on the vast crowd. One of the children killed that day was Hector Pieterson. The image of his friends carrying the dying child away down the road became an iconic image around the world of the unspeakable ignorance of the regime.

In 1976 I had been just one year younger than Hector Pieterson. I stood on that road on a beautiful sunny winter’s day 31 years later, the hum of daily life all around. On the corner was the Hector Pieterson Museum – the first museum built in Soweto. How forcefully it took one back to the appalling days of the old South Africa. How absurdly out-of-date those young white men in the pictures and video footage looked with their shaggy hair and bushy sideburns as they piled out of another armoured vehicle in their army uniforms to defend the indefensible. A mere 13 years after the end of apartheid they seemed unthinkable denizens of an horrific past.

Sfisio drove me home.

The next morning there was an engineer who was flying to Madagascar: that mysterious land where the cobbled streets of French villages lead to realms where lemurs dance through sentient forest – there were Madagascan iron-sand mines to be ‘engineered’ – so I got a lift to OR Tambo.

When Nelson Mandela visited New Zealand in 1995 he said ‘… the people of New Zealand played an important role in the elimination of the hated system of apartheid. I wish to take this opportunity to thank you for your support.’ He spoke especially of those who had opposed ‘the Tour’ in 1981. In prison on Robben Island Mandela and his fellow prisoners were denied access to news, but newspapers and radios were smuggled in and they drew heart from news of attempts in the outside world to influence the South African government.

The 1981 Springbok tour of New Zealand ran its long and bitter 56-day course. Only one game was called off due to protest – the game in Hamilton. In 1995 Nelson Mandela told Dame Cath Tizard, New Zealand’s governor-general, that when news of that cancellation reached the cells of Robben Island, ‘it felt like the sun coming out’.

Malaysian Airlines flight MH202 departed the Republic of South Africa on time at 1.40 pm on Thursday 21 June 2007.

The woman at Mahamba was right – it had cost me more than 10,000 rand to fly to Africa, but as the wheels left the tarmac I was richer than I had been before.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu once said:

God bless Africa

Guard her children

Guide her rulers

And give her peace.