There are moments in life in which the hubbub dies away and one stands silent before a numinous presence; moments in which one senses some profound meaning behind the realities of life; when one stands in awe before the wonders of existence.

It is this experience that one finds in the process of silent meditation or in other aspects of one’s spiritual activities.

However, the experience may interrupt one unexpectedly at other times.

I remember at the age of 16 spending a few days in a shabby fisherman’s hut high in the vast silence of the Southern Alps on the shore of Lake Coleridge. All around - the snow-covered mountains; before one - the serene face of the lake; above - the vast crystal blue sky, the call of shy water birds through the silence. I remember standing on the roof of that hut, my arms raised in awe, rapt and exultant before the glory of it all - transported to some realm far closer to God.

Great art can have the same effect on us as the wonder of nature. There is a recognised medical condition that fills hospital beds in Italy every year - people who just collapse on the gallery floor before the presence of beauty found in the art of that county’s greatest geniuses.

I remember at the age of 16 spending a few days in a shabby fisherman’s hut high in the vast silence of the Southern Alps on the shore of Lake Coleridge. All around - the snow-covered mountains; before one - the serene face of the lake; above - the vast crystal blue sky, the call of shy water birds through the silence. I remember standing on the roof of that hut, my arms raised in awe, rapt and exultant before the glory of it all - transported to some realm far closer to God.

Great art can have the same effect on us as the wonder of nature. There is a recognised medical condition that fills hospital beds in Italy every year - people who just collapse on the gallery floor before the presence of beauty found in the art of that county’s greatest geniuses.

Some of the same rapt awe which I felt in the Alps in my youth I found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York before Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Serena Lederer. I had seen the painting in reproduction many times and had never found it especially notable, but when I chanced upon the original I was awe-struck. I literally tip-toed towards it, transported by the great upwards sweep of the white brush-strokes that form the subject’s dress. I stood in almost reverential silence before the painting, carried by it to some deeper, silent place.

The silence of prayer, the splendours of nature, the glories of art - these are things that one might expect to produce such a rarefied reaction.

One might not expect the same reaction to . . . say . . . for instance . . . a few goats in a muddy concrete enclosure.

And yet . . .

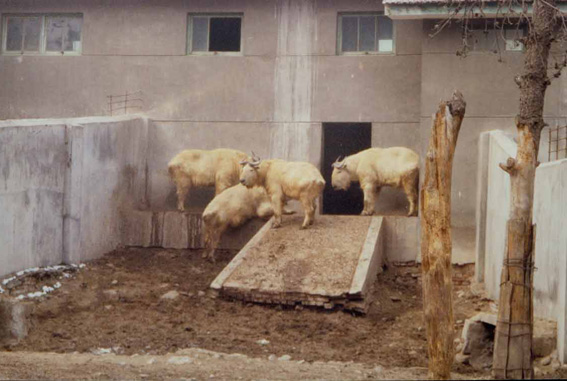

We were at a panda refuge in Zhouzhi county in central China. It was the depths of winter. We had been delighted by the pandas. They were extraordinarily endearing, magical, appealing. We had a little time left before we had to leave. We wandered around the rest of the refuge. There are a lot of endangered animals in China and a fair range of rare creatures were here.

Somebody came running down a bare-tree lined path - “Have you seen the golden ox?! Have you seen the golden ox?!”

We met another person exclaiming about this seemingly mythical creature, so we ran - we ran down wending pine-needle-covered avenues to find . . . budorcas taxicolor.

We stood before a concrete wall some eight or nine feet tall. In the wall was set a heavy wooden gate bound with iron. In the centre of the gate was a small barred opening. It put one in mind of nothing so much as a medieval fortress. We went up to the gate and gazed through the bars of the opening into the enclosure beyond - at which point we, as had been those who sent us here, were rapt up in an awe-filled silence, stunned and transfixed by the creatures within. As much as one might in front of the greatest work of art, the most sublime scene of nature’s beauty, the most lofty contemplation, one was silenced and humbled before some mysterious manifestation of a deeper and more meaningful realm which somehow had pierced through into our mundane, quotidian existences.

The people who had directed us here had snatched the name ‘golden ox’ out of the air to try to express their amazement and excitement at this unknown animal. What we were actually looking at was budorcas taxicolor, the Takin, technically speaking a goat-antelope. What stunned one was the sense of power that these creatures exuded. An air of unspeakable strength with just a hint of restrained violence hung over the muddy snow-dusted enclosure. As we watched, one butted the rump of another in a desultory manner. One would swear that the earth shook with the impact.

Before these huge, mythical, fearsome, powerful creatures shining with their golden fleeces, one could but stand in awe.

A small Chinese man appeared from somewhere and explained in fractured English something about these animals. The metal props and wires around the top of the concrete wall had, he said, been added because the animals had been jumping over the wall. The thought of the power needed to propel these vast animals over so high a wall was staggering. The great iron-bound gate they sometimes would batter down as well he explained. He left us in no doubt that these were fearsome and formidable creatures, dangerous to man and awe-inspiring - “bad animals” he concluded.

Of course hunting and habitat destruction has pushed the glorious takin to the brink of extinction.

I dream of a cold winter’s morning high in the mist-shrouded Qinling mountains. The water drops hang like myriad quiet diamonds on the bamboo leaves, and high on a precipitous slope, moving with the poise and strength and agility of nobility, a small family group of takin, the gold of their coats flashing in the muted tones of the dawn. And nobody sees them, and they move on, the click of their hooves on the virgin rocks the only sound.

*

Other articles about my trip to China:

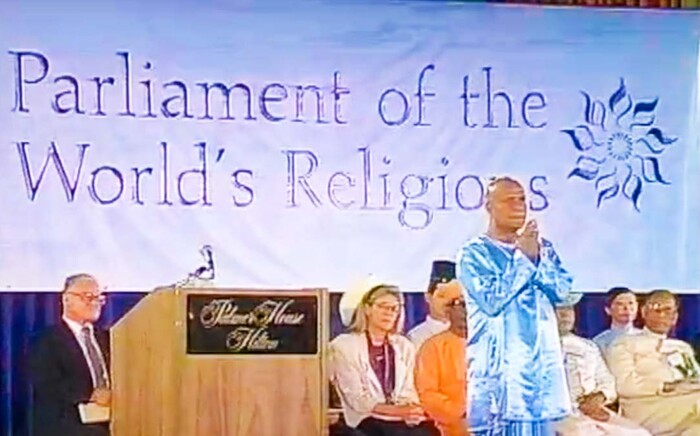

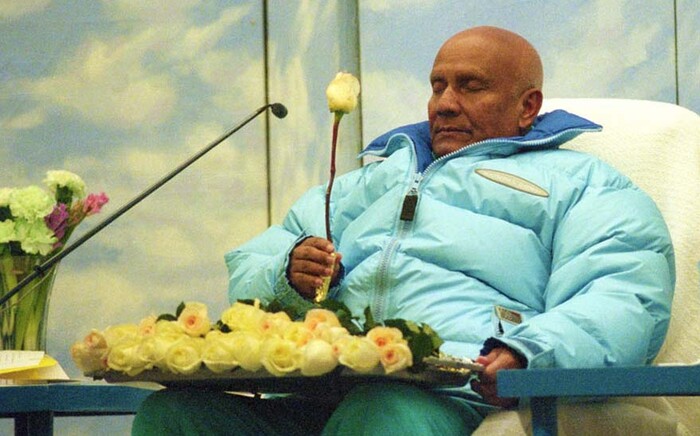

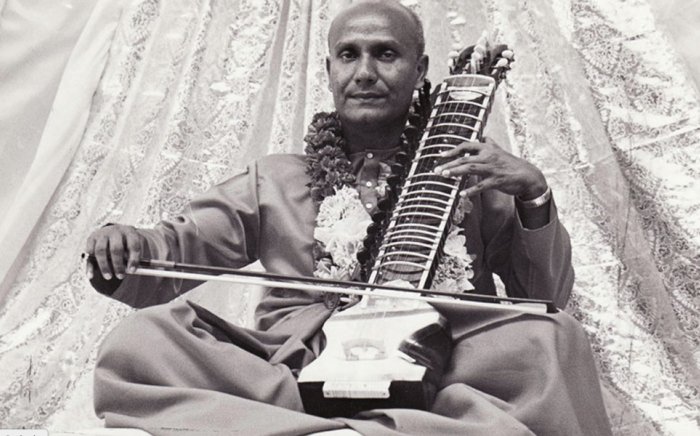

- In China with Sri Chinmoy

- East meets West

I remember at the age of 16 spending a few days in a shabby fisherman’s hut high in the vast silence of the Southern Alps on the shore of Lake Coleridge. All around - the snow-covered mountains; before one - the serene face of the lake; above - the vast crystal blue sky, the call of shy water birds through the silence. I remember standing on the roof of that hut, my arms raised in awe, rapt and exultant before the glory of it all - transported to some realm far closer to God.

Great art can have the same effect on us as the wonder of nature. There is a recognised medical condition that fills hospital beds in Italy every year - people who just collapse on the gallery floor before the presence of beauty found in the art of that county’s greatest geniuses.

I remember at the age of 16 spending a few days in a shabby fisherman’s hut high in the vast silence of the Southern Alps on the shore of Lake Coleridge. All around - the snow-covered mountains; before one - the serene face of the lake; above - the vast crystal blue sky, the call of shy water birds through the silence. I remember standing on the roof of that hut, my arms raised in awe, rapt and exultant before the glory of it all - transported to some realm far closer to God.

Great art can have the same effect on us as the wonder of nature. There is a recognised medical condition that fills hospital beds in Italy every year - people who just collapse on the gallery floor before the presence of beauty found in the art of that county’s greatest geniuses.