Sometimes a man gets to thinking . . . to musing. . . to mulling things over. . . and it generally ends in a painting.

I spent Christmas with my parents.

Lying under a tree, the clink of ice in a tall glass at your elbow, reading Harry Potter – perfect. “So it is Dumbledore who dies!”

When not lazing about, I chanced upon a photograph in the cupboard in the lounge - a photograph of a painting I had produced during an earlier Christmas break. It set me thinking.

Remember Ronald Lockley who wrote the seminal study on the behaviour of the wild rabbit? How I loved that book as a kid! He also wrote a number of autobiographical books. One was called The Island – about his days living alone on an island off the Welsh coast. How that appealed to me too!

Generations have read potted versions of Robinson Crusoe – never mind all Daniel Defoe’s biblical musing, we all just want to hear the story of a man living on an island. It seems that the man on the island must represent some deep-seated human aspiration – why else is he so appealing? Is he not in fact a symbol of the individual’s withdrawal into himself? Is he not, like the monk in his distant cave, the image of one who has withdrawn from the mundane life to know himself?

What we can forget as we think of the actual man on his physical island, is that at any time we can ourselves withdraw to the inner island, and, like Defoe’s Crusoe, there in the silence and peace, free from all distraction provided by those parts of our own nature which bustle about on the mainland, we can read the inner scripture – we can listen to the silence speak. The man alone on his island is the image that expresses that.

In 1997 I visited my brother in Germany. One day he took time off work and we went on an adventure to Maria Laach and Schloss Burreshheim. We were driving along the banks of the Rhine when Michael pointed out to me an island in the river. On the island stands a convent. The story goes, he told me, that in the days when Europe was emerging from the Dark Ages, the great hero Roland – glittering star of Charlemagne’s court – fell in love on the shores of the Rhine with Hildegunde, the daughter of a local prince. Later, when he had been called off to slaughter his fellow man in Spain, word came to Hildegunde that he had been killed in battle. By the time he actually returned to Germany to exclaim, as Mark Twain was to do, “the reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated”, it was too late. One account puts it thus:

“Hearing of Roland’s death, for days on end Hildegunde shut herself up in her little bower, and even her father’s gentle sympathy could not assuage her bitter grief. Weeks passed. Then one day the pale maiden entered the knight’s chamber, her grief quite transfigured. A last great convulsive sob had torn her lover’s name from her heart, had quenched the flame of sorrowing love for him, and now her soul was to be filled ever with the holy fire of the love of God.”

She withdrew to the island in the river and never spoke to Roland even on his return. How could she? She had found the island within – solitary, self-sufficient, separated from the world by the deep, placid waters of her own contemplation, unswayed by the allure and hubbub of the mainland.

The image stuck in my mind.

A few weeks later I was in Budapest marvelling agog at the glories of the Matyas Templom and weeping at the tomb of Gul Baba.

I have a certain dislike of museums but the Museum of Budapest History was undergoing alterations and so entry was free – I entered . . . and enjoyed it a lot. It was here that I learnt about the island in the Danube at Budapest called Margit Szegit – Margaret Island.

Margaret, born in 1242, was the daughter of King Bela IV of Hungary but spent her whole life in a convent. From the age of ten till her death at age 28 she lived on the island in the Danube that now bears her name.

Here again was the woman on the island.

The thing that I found out at the Museum of Budapest History which appealed to me most was that prior to Margaret’s arrival in 1252, the island was obviously not called Margaret Island . . . it was called Rabbit Island.

*

People often question the origins and symbolism of the Easter Bunny. The oft-cited rather basic fact that Easter is about new life and rabbits reproduce quickly is not in fact entirely true.

Before Ronald Lockley carried out his ground-breaking study of the behaviour of the wild rabbit, the strange fact is that very little was know of the life of this ubiquitous creature. Rabbits are crepuscular – being active at dawn and dusk. What nobody knew before – because nobody had bothered to look – was that they are also nocturnal, hopping about in the dark when no humans are there to see.

However, the idea that rabbits were only active at dusk and dawn lead our medieval forebears to conceive of the rabbit sitting patiently in his hole awaiting the rising of the sun, sitting in faithful expectation and hope for the return of the light. The rabbit thus became an image of Easter – not of Easter Sunday, but of Easter Saturday: of the Christian waiting in the darkness of Easter Saturday for the light and effulgent grace of the resurrection on Easter Sunday.

As the rabbit waits faithfully and with sure hope for the dawn, so too we wait for the dawning of divine grace in all its forms – the sort of preparatory waiting one might best accomplish free from the distractions of life – like . . . on an island perhaps.

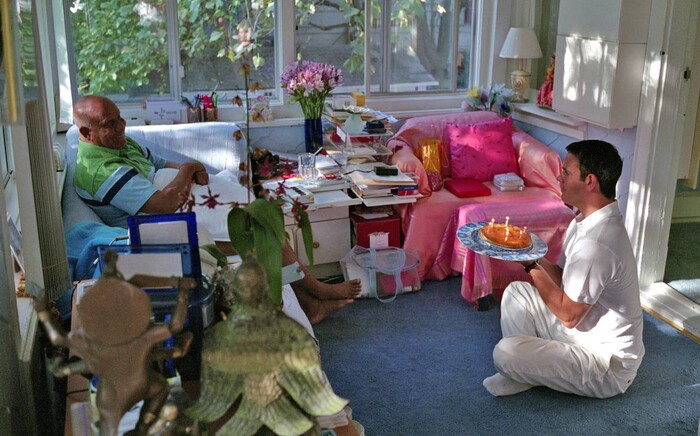

When I got back to New Zealand, these, and other, ideas coalesced into a painting – the photograph of which I just found in my parent’s cupboard.

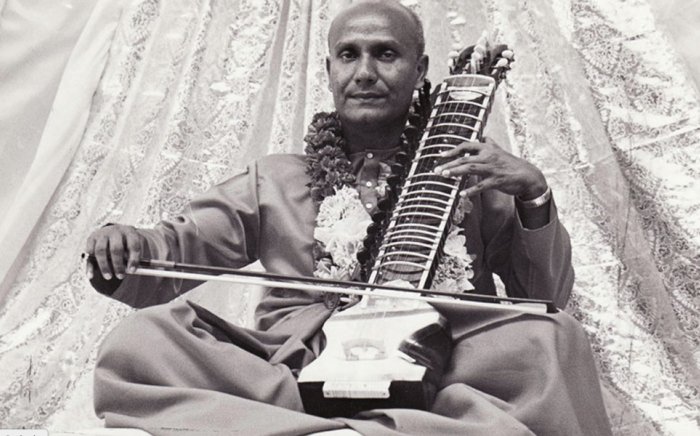

The painting itself sold about five minutes after the exhibition it was part of opened. It sold under the dignified and elusive name I had given it in the catalogue – “Budapest 1997” – but to me it had always been and would remain – “Maggie and the Easter Bunny”.