New Zealanders must be some of the least patriotic people on the planet, but, deep down, we like our little country quite a lot.

I live in a little wooden house. It is old. In winter it is cold as an ice-box. In summer the sun never shines in my bedroom window. The floor in the hall creaks, and when we stacked a lot of stuff on the porch the whole house leaned so much that we had trouble getting the front door open.

Two streets over from our house, in the same old neighbourhood, is the house of the Prime Minister of New Zealand. A recent study pronounced her the 43rd most powerful woman in the world.

Her house is a lot like ours.

Things like that make me love New Zealand.

In November 2005 I competed in the Kauri Run; things like that make me love New Zealand too.

There was a field of about 150. We ground up the little gravel roads of the north Coromandel Peninsula in three old buses. I looked around at my fellow competitors. They were hard men (and women). We stopped in a rough paddock behind the dunes of Waikawau beach.

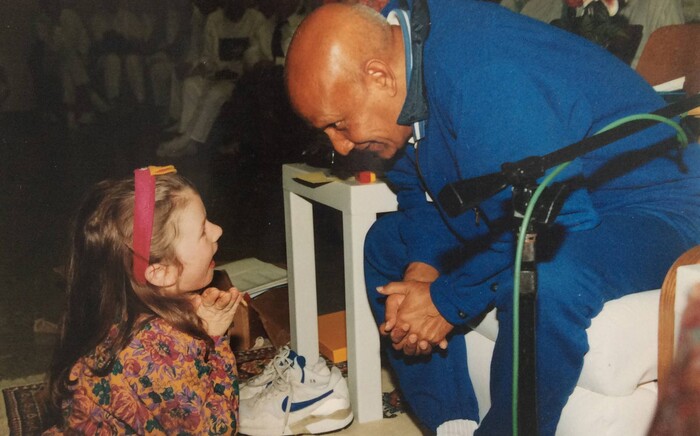

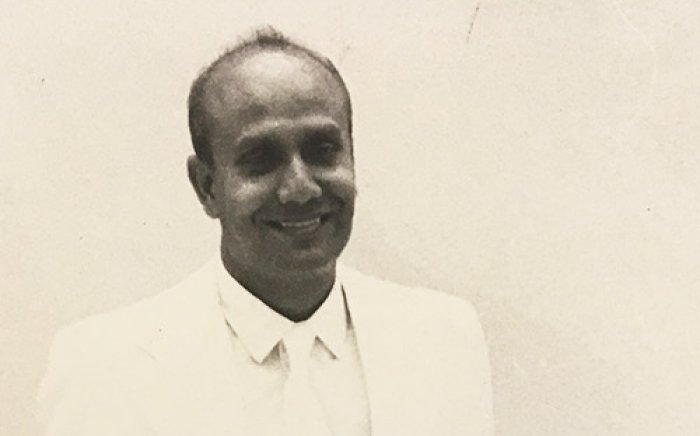

We had a short race briefing and then ‘Windy from Kennedy Bay’, the old kaumatua from up the coast, stepped forward for a karakia. He stood there, his glasses in his hands, and prayed.

There is no way that in New Zealand one could start a race with a prayer in English, but, hard men though we be - men who wouldn’t darken the door of a church except perhaps for a distant cousin’s wedding or if grandma died - here, in the temple of the great outdoors, we nod our heads and mutter ‘amene’ as Windy concludes. Out here in the rugged green at the start of a gruelling race we are solemn in the temple of shared humanity, of shared effort and self-transcendence, of silence before the mountain and the bush. As the race progresses, each will gulp down the Spirit into burning lungs with every ragged breath, feeling it power his quivering legs.

Our invocation of the unseen done, we trudge over the sandhills to the beach. It curves away around the bay - pristine, not a sign of humanity, two black oystercatchers the only sign of life.

The Maori poet speaks of a deserted land when humans have destroyed each other - “Ko wai rawa te tangata hei noho mo to whenua? Ko Turiwhatu, ko Torea, ko nga manu matawhanga o te uru!” (Who will be the people to live in your land? Dotterel and oystercatcher, the birds of the western shore!)

This scene is unpeopled, but that seems only right.

We wait. The surf dully thumps upon the beach. And the race starts.

*

The Kauri Run is organised by Adventure Racing Coromandel. It is a 25 km race but, given the terrain, the average time taken is over four hours. What makes this race unique however, is that not only does one get to run through the beauty of the Coromandel Ranges, but that for each competitor that takes part in the event a kauri tree is planted in the area through which the race passes.

A mature kauri tree

A mature kauri tree

The Coromandel Peninsula was once thick with these huge long-lived native trees. The trees - the largest in the world - can live over 4,000 years. Massive logging in the 1800s has gutted the bush of such giants. In these more enlightened times we try to restore what has been lost. Running this race helps that.

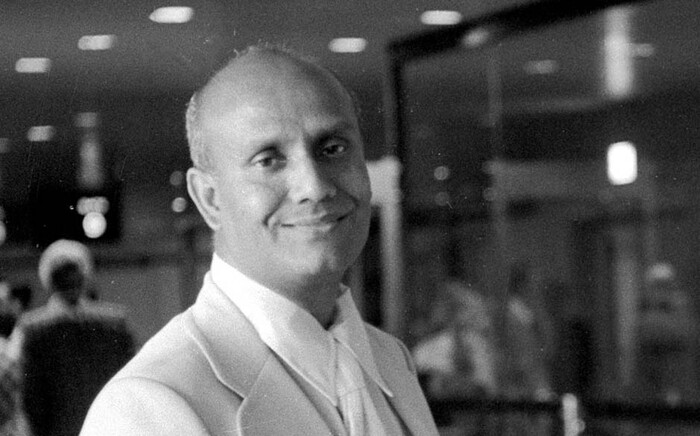

I once wandered with a friend into an unfinished building in the Far North. In its shadowy depths we met an old Maori carver who had been working on some intricate design. How long we spent with him I can’t remember. He stood there in his skimpy shorts and cowboy boots, his eyes closed, his head back as if he considered things in some realm beyond the dark interior in which we stood, his shock of white hair a halo around his head, and he spoke to us of the ‘old times’. He spoke to us of many things, but one thing he spoke of was the vanished kauri forests.

I once wandered with a friend into an unfinished building in the Far North. In its shadowy depths we met an old Maori carver who had been working on some intricate design. How long we spent with him I can’t remember. He stood there in his skimpy shorts and cowboy boots, his eyes closed, his head back as if he considered things in some realm beyond the dark interior in which we stood, his shock of white hair a halo around his head, and he spoke to us of the ‘old times’. He spoke to us of many things, but one thing he spoke of was the vanished kauri forests.

The few remaining huge kauri, he said, had been but average-sized trees in the days when the forest stretched unbroken from Coromandel to the farthest north. These vast trees grew so close together that a man would have to turn sideways in order to pass between them. A silent observer would hear the souls of the dead whistling between the trees as the departed wended their way north to Cape Rienga on their journey to the ancestral homelands.

These forests were so vast and bountiful and packed with life of all sorts and formed of trees so vast and ancient that they generated an energy that was virtually sentient. The great whales that cruised the coast in the (then) pure and silent depths could hear the voice of the forest, could hear it speak of the things of the land.

In 800 years or so the Maori destroyed their fair share of the forest, but one cannot but be amazed and impressed with the speed and energy and sheer effectiveness with which the pakeha threw himself into destroying the rest. With great ingenuity and determination and enormous hard physical effort our great grandfathers devastated our land.

Today, with some of the same qualities, people are trying to restore some of what we have lost. It will take a thousand years before the bush is as it was, but in the meantime how the beauty of what remains tears at our antipodean hearts!

In order to compete in this race I missed my niece’s 21st birthday. Her father’s ancestors arrived in New Zealand on the Philip Laing in 1848; her mother from Samoa much more recently, but I like to think that in a thousand years there will stand a tree, deep in an impenetrable forest, that marks Antonia’s birthday: another fragment of this country’s brief history.

The Philip Laing arrrives in Otago Harbour, 1848

The Philip Laing arrrives in Otago Harbour, 1848

The race starts along the length of the beach. At the far end there are some kids sitting at the base of the dunes beside the river that crosses the beach - “Good on ya! Good on ya!” they yell.

From there we head into the bush and up, up, up the hills. We cross and recross streams, we break out into open farm land. Down across the olive green of the bush, studded with the bright green on the punga fronds and dusted with the silver of the manuka flowers, down the rugged volcanic slopes, the vista extends to the turquoise sea and the islands of the gulf beyond.

On we run. The field quickly spreads out so one runs mostly by oneself.

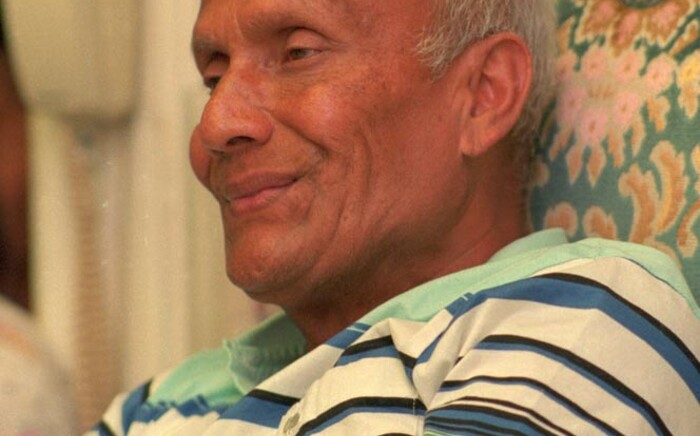

Gaining on Thomas McGuire

Gaining on Thomas McGuire

It is every childhood Christmas holiday rolled into one - the little rivers we camped beside, the deep silence of the bush, the endless hikes over grassy hills with the sheep and the skylarks beneath the endless blue sky of lost summers, the dusty back-country roads where my brothers had to wear cloths tied over their mouths and noses like young desperadoes to try to stop the dust aggravating their bronchial wheezing - ‘kittens in your chest’.

Running up these hills I wheeze myself but my heart flies. I sweep down the slopes like a bird - freedom, joy. I grind up the rough tracks, the sweat stinging my eyes and crusting white salt on my face . . . and inside I sing. I breath in the feeling of belonging, of running the fresh raw beauty of my country. Each rough clay farm track, each rocky, root-strewn bush trail, each river we splash through, each rough pasture, I know.

In any race you draw into yourself the distance covered - you end bigger than you started. I have raced 600 km and felt, by the end, my heart 600 km across. Here you draw in the full splendour of the natural world as well.

A few days after the race I chanced upon a poem that summed a little of it up:

Nature’s beauty helps us

To be as vast as possible,

As peaceful as possible

And as pure as possible.

Finally the course breaks out onto a road and the final dash into Coromandel township. Up the main street, round the corner to the school, one lap of the school field. On the finish line the race director stands, his arms spread in welcome. One cannot but run into his embrace. You collapse in his enfolding, congratulatory clasp. All is done.

Afterwards I lie on the grass in the sun - my legs have stopped quivering - as the other competitors come in. The atmosphere is relaxed, encouraging, genuine.

It was a long way. It was a hard race.

About half way through the race a young Maori man had been standing on the top of one of the hills - a marshal to make sure we took the right route. “Good going, Barnaby!” he had called out to me as I struggled up the hill towards him. I knew he had a list of competitors with him and had checked to see the name of competitor number 69 - but it cheered me inordinately none-the-less.

Years ago I went to art school with a girl from the USA. There were two things that amazed her about New Zealand - everybody says ‘thank you’ to the driver when they get off the bus, and people talk to the checkout operators in the supermarket.

The weekend following the Kauri Run, I was involved in organising a race at the Auckland Domain. We were up early that day heading out to set up. Slouching down the road, a little cloth bag over his shoulder - the Prime Minister’s husband.

What a great country.

Faith, Hope, Love - planting a kauri

Faith, Hope, Love - planting a kauri

Some links:The 43rd most powerful woman in the world - (the Forbes list of the most powerful women)

The Kauri Run Website

The poem quoted above

And a bit of a glossary for those unlucky enough not to live in New Zealand:

kaumatua: respected male tribal elder in a Maori community, keeper of knowledge and tradition

karakia: Maori prayer or incantation

pakeha: a New Zealander of caucasian descent

A mature kauri tree

A mature kauri tree I once wandered with a friend into an unfinished building in the Far North. In its shadowy depths we met an old Maori carver who had been working on some intricate design. How long we spent with him I can’t remember. He stood there in his skimpy shorts and cowboy boots, his eyes closed, his head back as if he considered things in some realm beyond the dark interior in which we stood, his shock of white hair a halo around his head, and he spoke to us of the ‘old times’. He spoke to us of many things, but one thing he spoke of was the vanished kauri forests.

I once wandered with a friend into an unfinished building in the Far North. In its shadowy depths we met an old Maori carver who had been working on some intricate design. How long we spent with him I can’t remember. He stood there in his skimpy shorts and cowboy boots, his eyes closed, his head back as if he considered things in some realm beyond the dark interior in which we stood, his shock of white hair a halo around his head, and he spoke to us of the ‘old times’. He spoke to us of many things, but one thing he spoke of was the vanished kauri forests. The Philip Laing arrrives in Otago Harbour, 1848

The Philip Laing arrrives in Otago Harbour, 1848 Gaining on Thomas McGuire

Gaining on Thomas McGuire Faith, Hope, Love - planting a kauri

Faith, Hope, Love - planting a kauri