The Te Houtaewa Challenge is a sixty kilometre (37 mile) race along Te-Oneroa-a-Tohe (also called Ninety Mile Beach). The race in 2006 started at 7.00 am on Saturday 11 March.

In the beginning - so they say - God created the heavens and the earth.

Now the earth was a formless void, there was darkness over the deep, and God’s spirit hovered over the water.

The Greeks tell us that the world is made of four elements - earth, water, air, fire.

We stood there at the start of the race in the cold, dark early morning. My teeth were chattering. Before us we could see three things - the earth, the air, the water. Stretching into the darkness - the flat expanse of the beach with the slight elevation of the sandhills on one side forming the skyline; the vast vault of the sky, dark but lightening; the whitecaps of the endless pounding ocean. The fire would come later.

Three Maori warriors approached down the beach towards us, stripped but for the piupiu round their waists that crackled with each step. They were armed with taiaha and proceeded in a menacing succession of prancing steps. Their eyes bulged and they let out fierce guttural shouts or hissing explosions of breath. It was the wero - the challenge - the challenge to see if we came in peace, if our intentions were good. Their ferocity certainly suggested that, if we did not come in peace, they had the will to leave a reasonable number of us clubbed to death on the beach.

a wero

a wero

Our representative went forward and picked up the rautapu that the lead warrior placed on the ground before us. Picking it up was the sign of our faith, of our good intent.

The challengers withdrew into the darkness.

The beach before us was empty.

The guardians of the endless sand had given us their licence to run.

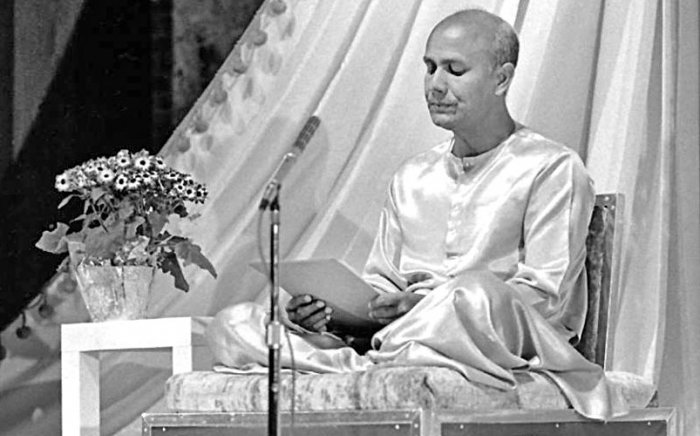

We prayed together - calling on the atua to bless our journey, to ease our passage through the day.

And into the darkness we ran.

The earth was soft, newly created, recently risen from the waves, each footstep sank a little into its virgin surface. The ocean crashed upon the land to our right. The sky was brightening fast.

As Homer said:

Rat.

Pearl.

Onion.

Honey:

These colours came before the Sun

Lifted above the ocean,

Bringing light

Alike to mortals and Immortals.

And through this falling brightness,

through the by now:

Mosque,

Eucalyptus,

Utter blue,

Came. . .

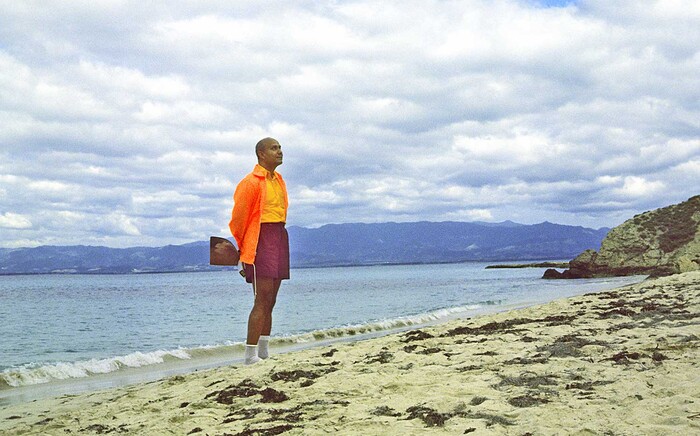

. . . came here a single running man, the only vertical in a world of huge horizons.

And the fire came - a great fiery ball of nuclear fire rising above the horizon.

The sky was utter blue; the sun burned; the quaternity was complete - earth, water, air, fire.

And always: movement - the ever-onward thump of foot-fall against sand, the ever-steady rasp of air into lungs, the steady drip of sweat that fell past my left eye from the peak of my hat, the ever-mounting flame within - the aspiration that carried me onwards down the beach towards Ahipara - Ahipara: a name which means ‘sacred flame’ - for here of old the sacred flame was maintained. I run - Deep calleth unto deep. O my God I will remember thee from the hill Mizar.

The first nations of the Americas knew about running. The Navajo speak of running as ‘joining in the motion which is at the heart of life itself.’ As everything moves - from the cascade of sub-atomic particles to the billowing of the galaxies - so we too move. With effort and inspiration we move down the beach.

That which does not move is dead: that which runs is most alive.

Gerard Manley Hopkins, the great nineteenth century Jesuit poet, knew that it was in movement that nature expressed itself -

sheer plod makes plough down sillion shine

But as the movement continues for hours, it wears us down. No longer the running man of fire beneath the sun, one’s head hangs and one stares at the plankton-slimed water on the sand. There are a million little holes in the water-covered sand. Every so often a little geyser of water spurts from one a few inches into the air - somebody down there does not appreciate my race.

The running is hard. It reduces us. It whittles away at our pretensions. Sweaty, sticky, exhausted we seem less than we were.

But Fr Hopkins foresaw this too:

and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermillion.

It is in the apparent fall, it is in galling ourselves in the exhausted push along the beach, that we discover the golden fire within us. And it breaks from us:

A heart’s-clarion! Away grief’s gasping, joyless days, dejection.

Across my foundering deck shone

A beacon, an eternal beam. Flesh fade, and mortal trash

Fall to the residuary worm; world’s wildfire, leave but ash:

In a flash, at a trumpet crash,

I am all at once what Christ is, since he was what I am, and

This Jack, joke, poor potsherd, patch, matchwood, immortal diamond,

Is immortal diamond.

*

After the race, after I washed the grime and pain of the day away, and after I received my due reward, and after I ate - my friend John and I headed up the hill that presides over the end of Te-Oneroa-a-Tohe - the beach of Tohe. There lie the dead in their narrow beds of earth - the ancestors, the tupuna.

There, while the sun sank into the ocean and the moon shone down upon the great sweep of the beach below, we met Mr Tepania. He told us about the people in that cemetery - who was married to whom, who had worked in the Post Office, who had dug kauri gum and was famous for walking everywhere, who were the staunch Catholics and whose ancestors came from Dalmatia.

As we descended the hill, Mr Tepania was sitting beside a headstone - he had come to talk with his father.

The sad, secular world in which we live has much to learn. The word ‘profane’ comes from the ancient Greek and means ‘outside the temple’.

Fortunate are those who find themselves in that temple whose dome is the vaulted air, where-in one kneels on the gentle sand and is baptised by the passing tide. One need but bring a flame with which to worship God.

***********************************************************************************

Bibliography

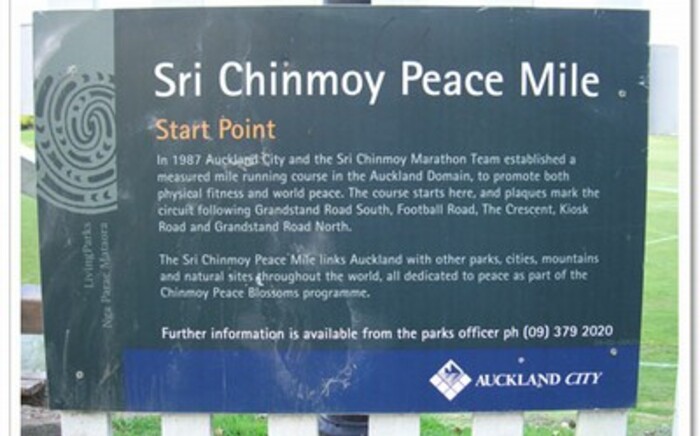

The Te Houtaewa Challenge

website

My other writings about this so-special race can be found

here and

here

a wero

a wero